The stories of the St. Mark cycle are well represented in the church’s mosaic decoration.

The stories of the St. Mark cycle are well represented in the church’s mosaic decoration.

Internally and externally the episodes regarding the Saint’s life and his body are presented in three main cycles with different iconographic versions.

Inside the church the Saint’s glory, the writing of the Gospel and evangelisation of the Veneto area are celebrated.

He is portrayed in isolation in the bowl-vault above the central entrance. This mosaic was done in 1545, probably to a cartoon by Lorenzo Lotto or, according to recent attributions, by Titian. It replaced the previous Pantocrator in the first half of the 16th century. St. Mark, in liturgical vestments, is welcoming the faithful with open arms.

Going into the church by the main entrance there are numerous references to St. Mark. On the internal wall above the main entrance the evangelist is in the lunette of the Deesis together with the Virgin in the function of intercessor with Christ.

The portrayal of the Saint at the top of the central apse of the presbytery has a more politico-religious accent. Here his figure functions as a trait d’union with St. Peter on the left and St. Ermagoras on the right. He extends a hand towards St. Peter, alluding to the gospel received from him, and proffers the evangelical text to St Ermagoras who is in an attitude of reverent respect. Isolated on the extreme left is St. Nicholas of Bari who also has a political significance.

These early 12th century mosaics are the oldest in the church. The century of struggles for ecclesiastical supremacy between the two patriarchates of Aquileia and Grado had just finished with the victory of the latter, supported by the Republic. It appears that Grado, defined as the new Aquileia, took over the traditions and privileges of the latter’s church, of which the chief aspects were its founding at St. Peter’s behest by St. Mark and its first bishop being St. Ermagoras.

St. Nicholas of Bari also comes into this dialogue, though in a different perspective. His body was stolen from Mira di Licia between 1099 and 1100. Heated discussions arose about putting his remains in St. Mark’s next to the Evangelist’s tomb. When it was decided to put them in the Lido Monastery his image, as a substitute, was included in the mosaic. Moreover, in this historic crisis, it seems that the patriarch of Grado had to take up permanent residence near the precious relics at San Nicol� di Lido where the new saint became his symbol. In placing him in the mosaics next to St. Mark, indubitable symbol of the doge’s power, the idea was to show everyone that patriarch and Doge coexisted peacefully in the doge’s basilica.

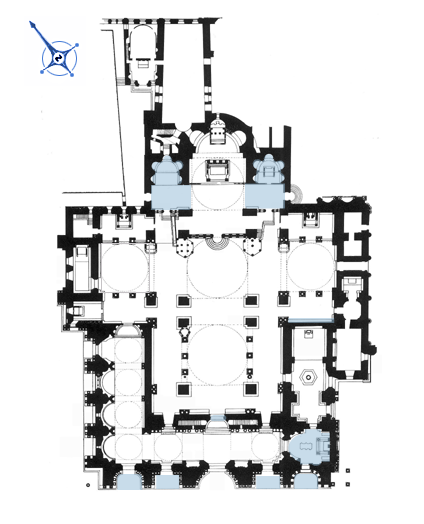

MAIN PORTAL AND CENTRAL APSE

Political values are again evident in the great biographical cycle of St. Mark dating to the first half of the 12th century and situated in the side chapels of St. Peter on the left and St. Clement on the right of the presbytery. It is the same subject treated in the present day Zen chapel, the old “sea gate” on the right of the central atrium.

The differences are perceptible first of all in the language: in the presbytery the mosaics have a notable stately accent that is quite far from the rather discursive and popularising mosaics of the Zen chapel.

The themes too are very different. In the presbytery chapel there is an insistence on the apostolic origins of both Aquileia and Alexandria where St. Mark was said to have been sent by St. Peter to preach and baptise and where he died, whereas the mosaics of the Zen chapel highlight, over and above all this, the themes of the divine praedestinatio of St. Mark, patron saint of Venice. In both cases there is agreement with regard to the representation and death of the Saint in Alexandria and his removal to Venice. But in the presbytery chapel the accent is always on the courtly and State occasion: reception by the entire episcopate of the lagoon area with the patriarch of Grado at the centre and the six bishops (Caorle, Eraclea, Equilo, Malamocco, Olivolo, Torcello), elements not found in the story of the traslatio. The Doge himself (Giustiniano Particiaco) with his entourage recalls the mosaic of emperor Justinian in the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna.

CHAPEL OF ST.PETER

CHAPEL OF ST.CLEMENT

ZEN CHAPEL

Other mosaics dealing with St. Mark that supplement the presbytery story are on the vault of the extreme right section of the atrium. This is the point where the “holy way” of the ducal procession, arriving from the pier, entered the church: the “sea gate “.

It was only at the dawn of the 16th century that this area was occupied by the building of the Zen chapel which closes one of the most significant access points.

The preferential themes accentuated in this area are taken from the legend of the praedestinatio of the Saint. The angel appears to him during a shipwreck while he is sailing the lagoon from Aquileia towards Rome and thence to Alexandria. The ship was at sea in correspondence to the present day site of St. Mark’s Church. The angel told the Evangelist that after his death his body would rest there.

Where the Piazzetta is today there was originally the Byzantine mandrachio, the canal-port common to upper Adriatic coastal centres. The early Venetian vessels used to berth in the place where the Saint’s body was disembarked from Alexandria and where the church was built. It was a sacred place, a place in which the seat of political power, the Ducal Palace, was legitimised by divine will in the name of the State’s patron saint, in the name of St. Mark. The martyrdom episodes in the Zen chapelfaithfully reflect the story of the passion of Mark (Tower of Alexandria, i.e. the Lighthouse; The Saint Struck and Beaten on the City Streets; Beheading in the Meadows of Boucolis, etc.), narrated in popular language. The people entered here and read the other biographical chapters of the traslatio in the Piazza mosaics.

INVENTIO

The last episode is the Inventio, the enormous mosaic page originally next to the Treasury door. It depicts the 1094 prayers and fasting petitioning the Lord, at the behest of the Doge Vitale Falier, in order to discover the whereabouts of the Saint’s body which, after building of the just completed present church, were quite unknown. Legend has it that St. Mark indicated the position by extending his arm from a pillar, the one that is today on the left of St. Clement’s chapel. Amid aristocratic and popular celebrations the local bishop and the Doge definitively placed the saint’s body beneath the high altar where it remains today. The great mosaic, typically western in both stylistic language and size, is a precious chapter of Venetian history at the end of the 12th century for both liturgical customs (altar, priestly vestments and a portrait of the local bishop Domenico Contarini) and civic customs (Doge Vitale Falier, procurators of St. Mark’s, sons and daughters of the nobility, men and women of the people) and for its depiction of the church with the two pulpits, the women’s galleries and the internal bowl-shaped cupolas, antecedent to the external wooden cupolas covered in sheet lead.

MAIN FACADE

On the exterior of the main fa�ade are the final episodes concerning the Saint. The mosaics should be looked at starting from the first arch underside above the right portal which shows the Recovery of St. Mark’s Body (around 1660) by the VenetiansBuono da Malamocco and Rustico da Torcello in 828 in Alexandria where the saint was buried after his martyrdom. Next, to the left above the high portals, are the Arrival of St. Mark’s Body in Venice (approx. 1660), the Reception by the Doge of the Lords(approx. 1728-29), and the Processional Transfer of the Saint to the Basilica, the only antique 13th century mosaic because the others, though they observe antique iconography, are later re-workings of the 17th and 18th centuries. The lower mosaic register celebrates the Presence of St. Mark’s Relics in Venice and in the Church..