It was only in the second half of the 16th century that musical instruments (other than the organ) started to take on a stable role in liturgical functions. There was a particular preference for wind instruments in St. Mark’s Basilica.

It was the start of a new musical concept that put the two technical realities of chant and instrumental music on the same plane. Numerous instrumental and vocal combinations were experimented in St. Mark’s. In the forefront was Andrea Gabrieli, who by reaching evolved polychoral writing, was able to equalize the instrumental and vocal languages.

FURTHER INFORMATION

The history of the Venetian musical civilisation ran parallel with that of St. Mark’s music chapel and the cultural life that grew within it.

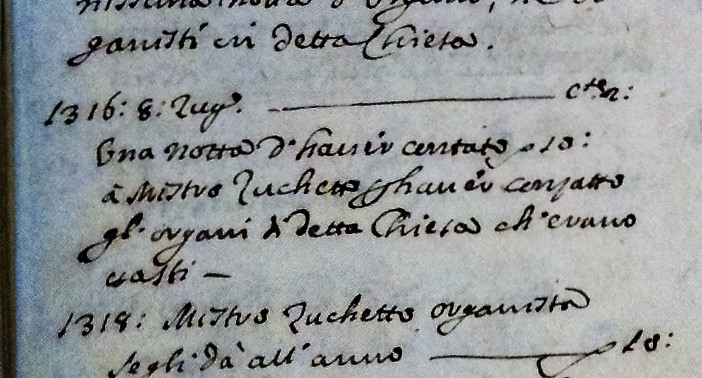

Following the basilica’s consecration in 1094, the first important news in the music circle dates to June 8, 1316, the year a document was written, wherein we read: “Desemo a Maestro Zucchetto ducati 10 per onzamento degl’organi grandi de San Marco li quali era vastadi” (“We’re giving Maestro Zucchetto 10 ducats for maintenance of St. Mark’s major organs”). This date marks the start of the “first musical era” of the basilica, distinguished by the presence of fourteen organists. In 1489 Fra Urbano placed the left organ – called the first organ – and Francesco Dana inaugurated it on August 20, 1490. This brief period, commonly known as the “second era“, is characterised by the simultaneous presence of two organists to who the important figure of the Maestro of the Chapel, Fleming Pietro de Fossis, was added in 1491. He also had the job of instructing the choristers. It is the beginning of the so-called “third era“.

By the will of the Venetian government with its decree of June 18 1403, the Chapel of St. Mark was also a music school.

In the beginning, “otto putti veneti diaconi” (“eight child deacons of Veneto”) were admitted to learn “to sing well” with the gift of one ducat a month.

Along with the death of the Flemish maestro in 1527, the responsibility for instructing the choristers was handed down to his successor, Adriano Willaert, who personally was in charge of it until 1562. The Chapel of San Teodoro was assigned to the school.

A second chant school was established in 1577 at the service of the church, at the Seminary of St. Mark. Opened in 1580, its seat is Primicerio Palazzo.

The ducal seminary was transferred to Sant’Antonio di Castello, to the building called Sepdale di Messer Ges� Cristo, in 1591.

In the meantime, former chant maestro Baldassare Donato was named Maestro of the Chapel of St. Mark. In the clauses regarding his appointment, Donato had the duty of teaching the seminary’s clergymen figured chant, plainchant and counterpoint.

The two schools were very active and numbered excellent pupils. One for the “zaghi di chiesa” (“younger priests of the church”) and the other for the “pupils of the ducal seminary”, they educated choristers, players and composers sought after by the musical world of the time.

The most famous pupils of Adriano Willaert were not Venetians. Cipriano de Rore was Flemish, Gioseffo Zarlino was from Chioggia, Contanzo Porta was from Cremona, Claudio Merulo was from Correggio, Francesco della Viola came from Ferrara and Andrea Vicentino was a native of Vicenza.

Baldassare Donato and Andrea Gabrieli, two brilliant composers who were Venetian by birth, became leaders of the progressive movement tending to striving to enhance the value of local culture.

Zarlino, who did not approve of his didactics, did all he could to break up the small chapel where Donato was carrying forth his new musical ideas.

The conflict between Chapel Maestro Zarlino and Donato noisily and publicly erupted during the feast of St. Mark, a solemn day of festivities, with the protest of the choristers and their revolt against the higher orders.

Baldassare Donato’s animated opposition continued with the activity of one of his followers, Giovanni Croce, to whom he had taught chant and composition. Croce’s work developed under the imprint of the maestro, above all in his madrigal and motet writing and for double choir. In 1565, at the age of eight, he was presented as a contralto in order to be taken into the Chapel of St. Mark, at the time under Zarlino. In his capacity as chorister, he benefited from the music taught to the young men in Donato’s small chapel. He witnessed the above-mentioned incident between his maestro and Zarlino at the age of 12. He was named deputy maestro in 1594 on Donato’s suggestion, who in the meantime went on to manage the Chapel following Zarlino’s death.

Doge Marino Grimani wanted an energetic and strict successor on Donato’s death, who he saw precisely in the person of Croce.

The other leader, Andrea Gabrieli, worked together with Donato to increasingly break away from the Flemish counterpoint tradition. Gabrieli gave organ and composition lessons at San Geremia. Afterwards, he established himself at San Samuele with his appointment at St. Mark’s, where he continued his important teaching activity.

By an odd coincidence, the three musicians who opposed the Flemish movement in the wake of Donato and Gabrieli were all named Giovanni: Croce, Bassano and Gabrieli. The vitality of the trends that these three musicians depicted brought about a succession of pressures on the Venetian environment, to such an extent that they forced Cipriano de Rore, the new Flemish maestro named at St. Mark’s Basilica, to waive the position and go to work for Ottavio Farnese, the duke of Parma and Piacenza. The same thing happened with Flemish movement promoter Claudio Merulo, who in 1584 had to move to Parma with his family.

Nonetheless, Zarlino remained the charismatic figure of the traditionalist movement, representing it influentially both officially and in his capacity as composer and theoretician.

The “fourth musical era” of the basilica, characterised by one maestro, one deputy maestro and two organists, reached the peak of its splendour with Claudio Monteverdi, who took leave of the Mantuan court to replace Giulio Cesare Martinengo in 1613.

Monteverdi’s successors developed their intuitions and the entire XVII century progressed with the musician from Cremona as its unfailing reference point.

The “fifth era” characterised by a strong instrumental presence in the basilica, opened the new century. The chief exponents were Antonio Lotti and Antonio Biffi, but composers of the calibre of Benedetto Marcello and above all Antonio Vivaldi were not remote and made their important influence felt. Chapel musicians increasing experimented new sound dimensions ahead of their time. The century closed under the guidance of highly famous maestro and composer, Baldassarre Galuppi, known as “il buranello”.

The fall of the “Serenissima” in 1797 saw a large downscaling of the importance of the Chapel. While its players remained very vivacious – with their tireless production of new music – the “Marciana” became the patriarchal chapel and the new curial management was not always generous to this ancient and glorious institution. The XIX century passed with all manner of restrictions. The orchestra was gradually reduced until its disappearance at the end of the century and the chapel was deprived of its sharp notes.

The “sixth era” began with Antonio Buzzolla, active in the basilica from 1850 until 1870. This period was characterised by a desire to return to the past and by a gradual but inexorable fresh blooming of chapel music accompanied by the organ alone. In 1890 a formation of treble voices was added permitting the execution of the ancient sixteenth century music. Here too, as throughout Europe, the fascination of the Gregorian school was rediscovered. New composers led mainly by a young Lorenzo Perosi, active at S. Marco from 1894 until 1998 proposed a new way of writing music in a more austere way closer to the ancient Christian monodic patrimony.

Venice’s unusual geopolitical position and its continuous exchanges with various European and Mediterranean cultures made St. Mark’s Chapel a universally recognised point of reference for a long period, which unquestionably contributed to making it one of the world’s music capitals. From the second half of the 16th century and for the most part of the 18th century Venice was one of the most important music centre. But even afterwards the chapel’s function as proposer of ever-newer ideas remained a constant.

This unique group is one of the few remaining in Italy to regularly perform polyphony of merit during the liturgical service, in continuity with its very own tradition. It has been regularly present at the basilica’s most important functions for centuries without interruption, and this cultural heritage, this modus cantandi, is immortalised in an unmistakable style that is continuously fuelled under the vaults of St. Mark’s at the source of charisma of the Evangelist artist.

St. Mark’s Chapel is one of the living symbols of Western music tradition. Aware of this, in the 19th century its maestros started to recover the oldest patrimony, which also sprung forth within its walls, with the intention of restoring and keeping alive the enormous wealth that the past has handed down us. Whoever enters the basilica today can listen to music written as far back as eight centuries ago or music written only a few weeks old.

At present: Chapel master, Marco Gemmani; Chief organist, Pierpaolo Turetta.